The colourful Values Map was designed by the Common Cause Foundation, but draws (with permission) on the original research of Professor Shalom Schwartz, a social psychologist and cross-cultural researcher who developed what’s known as the Theory of Basic Human Values. This theory is the most widely studied model of values and provides one important foundation stone for our work at Common Cause. Although it has its limitations (like all theories!), we believe it can prompt us, as people and organisations motivated by social and environmental justice, to consider the importance of values in building public demand for systemic and durable change.

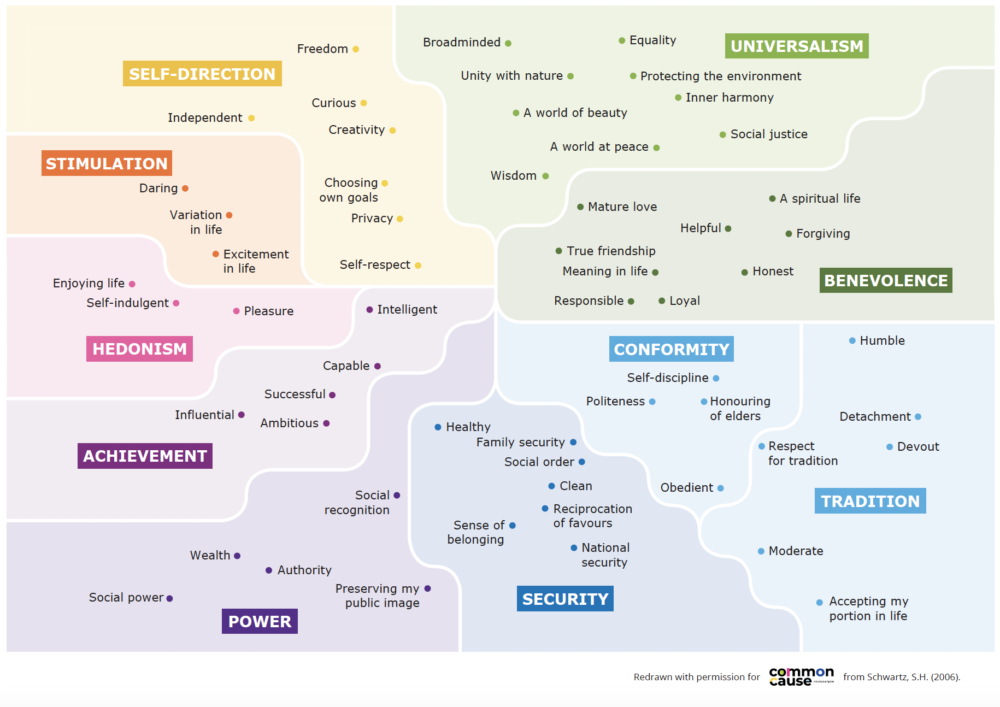

As you can see from the map, Schwartz’s model includes 58 individual values divided into ten broad values groups. These values have been identified by social psychologists drawing on an understanding of the requirements for human beings to survive as biological organisms. They represent different needs that we have as living beings, as well as needs we have as members of coordinated social groups, including the survival and welfare needs of the group itself.

The ten values groups are defined as:

The relative importance that we place on different values influences our actions. We draw – sometimes consciously, more often unconsciously – on different values to guide our behaviours and attitudes. Different values are likely to come to the fore when we make decisions in different contexts. For example, our impulse to help a stranger in difficulty is likely influenced by our Benevolence values. But our hesitancy to help this same stranger may arise from Security values.

The importance that we place on certain values is influenced by our experience of the society in which we each live – both in the moment, and over the longer term.

Whether or not we actually offer help to the stranger may be influenced by whether we have been recently reminded of the importance of kindness – perhaps by receiving kindness ourselves. But is also likely to be influenced by factors which have exerted longer-term influence – how we were parented, norms within our peer group, or the kind of education that we’ve had, for example. We call the short-term effects “priming effects” and the longer term effects “dispositional effects”

Researchers have found that some values conflict with one another, whereas others are more compatible. It is these dynamic relationships between values which gives us the structure of the map itself. When two or more values are close together on the map they are more compatible, whereas when they are far apart they are likely to conflict. For example, pursuing achievement values in the bottom left of the map typically conflicts with pursuing benevolence values in the top right. A motivation to achieve success or influence for yourself tends to lessen a motivation to enhance the welfare of others. But pursuing both achievement and power values, which are next to each other on the map, is usually far more compatible. Seeking to gain personal success is often strengthened by actions to enhance one’s social position or power over others.

Going back to the stranger in need, evidence suggests that if we’ve just seen a billboard advertising clothing (Power values), we are less likely to offer help (Benevolence values). This is a priming effect and is shorter-term. But if we’ve been brought up in a culture where there is a great deal of advertising and where we have been repeatedly, and perhaps unconsciously, reminded of the importance of Power values, then we are less likely to help the stranger regardless of the specific environment in which we encounter this person.

So people differ in the importance that they place on different values, influenced by their upbringing, their education, their friendship group, their political context etc. However, following decades of research and hundreds of cross-cultural studies with survey samples including highly diverse geographic, cultural, linguistic, religious, age, gender, and occupational groups, it seems that the structure of the values map is remarkably consistent across different cultures – leading some (very bold!) psychologists to suggest that it is ‘universal’. Although different cultures champion or discourage different values, on the whole, the majority of people across the world regard benevolence, universalism and self-direction values as the most important and power and stimulation as the least important.

For more information on the research behind the map, see this overview of the Schwartz Theory of Values.

Is there a way to fundraise without being in direct competition with other charities?

Are your communications engaging people as citizens or consumers?

Exploring some of the challenges posed by the pressures of short-term fundraising

Reflecting on intrinsic motivations to volunteer

More information on the two values surveys that Common Cause draws on in its work

Further information on the texts used in the study with WWF and Scope

A summary of results from research into priming values