The public tide is turning when it comes to climate action. We know that more people than ever before consider the climate and nature crisis to be real and of the utmost importance to tackle. Despite little mention of climate change during election campaigning, we have seen MPs elected from across the political spectrum who recognise and advocate for the need for bold climate policies. And importantly, we’ve seen many climate sceptics and naysayers lose their seats. So, what now?

Today, the King’s Speech will take place, where the priorities of the new government will be outlined. According to a press release from the Prime Minister’s Office, we can expect a speech focused on how Labour will seek to build “a bedrock of economic security, to enable growth that will improve the prosperity of our country and the living standards of working people”.

A focus on catalysing economic growth was to be expected; indeed, this framing is mirrored in much of the Labour manifesto talking about everything from education to prisons to energy. We hear time and time again the phrase ‘green prosperity’, of how climate action will help to tackle rising energy bills, create more jobs and help the UK become independent from the likes of Russia’s Putin.

Just this week, Ed Milliband, the new Secretary of State for Energy Security and Net Zero, announced plans for a “UK solar rooftop revolution”, where millions of homes across the country will be fitted with solar panels; the rationale being that this will cut household bills whilst simultaneously helping to fight climate change.

We could debate why Labour has chosen this ‘win-win’ framing. Perhaps it’s in response to the populist right’s opposition to urgent climate action through reference to the cost that they claim will be laid at the feet of citizens. Or perhaps it’s because, as proponents of the neoliberal project, the values that underpin an economic growth framing are in keeping with the values they wish to reinforce through their time in power. Either way, it’s important to acknowledge that this framing has huge consequences in terms of how the British public are encouraged to think, feel and act on climate change – and, at the same time, a vast number of other social and environmental issues.

Saying what’s popular

We are a nation – a world* – obsessed with growth. This narrative is woven into so much of our daily lives, whether it’s the latest stats on GDP we hear on the nightly news, to the implicit cues about the importance we place on our own wealth creation through the TV shows we watch. We find ourselves today facing an existential threat never before experienced, which is partly due to our collective and individual desire for infinite growth, and our addiction to the lifestyles that growth affords a small number of people. All the while inhabiting a finite planet, with ever-depleting ‘resources’ (I say resources in quotations here, as the very label implies an extractive, separatist relationship between human beings and the living ecosystem of which we are apart) and mounting pressures on fragile planetary boundaries.

When politicians repeatedly make decisions to frame climate action (and numerous other pro-social and pro-environmental policies) as desirable because it helps the country’s bottom line, or makes individual households wealthier, it further strengthens a narrative that what we should strive for is further growth. That what we need in order to get out of our current predicament is more of the very thing that got us here in the first place.

It goes without saying that governments sometimes need to do things to save money, and that is not, in and of itself, a bad thing. However, when the money-saving case is what politicians (and many NGOs) lead with in public-facing communications, they risk creating a scenario where, should a pro-environmental or pro-social policy actually cost money, they may not be able to rely on the public’s support. Climate justice becomes conditional on the reality that it won’t negatively affect the possibility for growth; that it isn’t financially ‘inconvenient’. The message of green prosperity feeds a belief that we don’t really need to do anything that drastic to solve the climate crisis, all that is required is a few tweaks here and there.

Making popular what needs to be said

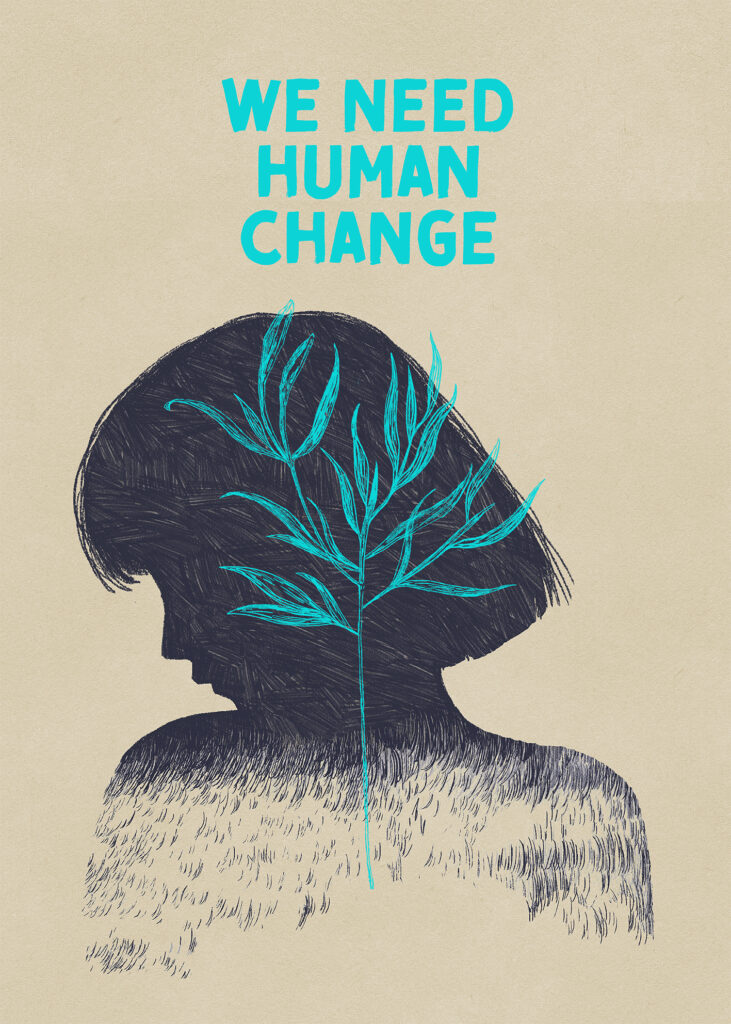

To be in with a chance of making the deep changes necessary to disrupt the current trajectory humanity is on, we need to work to strengthen different priorities within the cultural landscape.

Research shows that the majority of people in the UK place greater importance on equality, justice and protecting the environment than they do on wealth, power or success. This is despite the abundance of cultural cues we receive all day everyday that remind us that what we should be concerned with is how wealthy, successful, powerful, influential, productive and popular we are. We have an opportunity, not to manipulate and change people’s values, but to speak and legislate in ways that honour people’s existing values, unlocking (currently under-appreciated) sources of public concern.

Margaret Thatcher spoke of how she saw her role as Prime Minister to use economic policy to change the heart and soul of the nation. In other words, to change what we, as a country, value most. She was effective, which is one reason why we find ourselves in a situation today where everything has to be justified in terms of financial gain. My hope is that MPs today, who care deeply about the interconnected crises we are facing, have the same visionary outlook. They recognise the need to reverse this situation, and see a fundamental part of their role as being to help bring about a cultural level ‘change of heart’. That aim can begin by getting very intentional about the policies we support, recognising the influence they have on shaping ways we each think and feel about one another and the non-human world, and importantly, considering the deep narratives we reinforce when we advocate for these policies to the public.

*I want to acknowledge here the communities across the world who have historically resisted, continue to resist and warn against the damage of the growth paradigm.